Data Mining

Your personal information is a gold mine to marketers wanting to sell you goods and services. And data mining is the way companies harvest this wealth of information. It can protect you from fraud, but it may also expose your private information.

Data mining uses automated computer systems to sort through lots of information to identify trends and patterns. It is often used to look into people’s behavior based on past purchases, where they routinely travel or the events in their lives. The practice raises ethical issues for organizations that mine the data and privacy concerns for consumers.

Mining large collections of data can give big companies insight into where you shop, the products you buy and even your health. Just about everyone leaves a big enough data footprint worth mining. Business analysts predict that by 2020, there will be 5,200 gigabytes of information on every person on the planet, according to online learning company EDUCBA.

That’s a lot of information about you. Just one gigabyte can contain 1,000 short novels, according to the California Institute of Technology.

All this information helps businesses target you as a potential customer. And it may also make your personal information a target for unethical businesses or cybercriminals. But there are things you can do to guard your privacy and minimize your risks of unscrupulous data mining.

What Is Data Mining?

Companies in the United States are allowed to collect digital information about people from a variety of public and private sources. They use this data to try to create profiles of individuals or targeted groups of people to benefit their business.

Data mining digs through all this information to discover patterns and relationships. Results from analyzing past patterns can be used to make predictions about the future. This allows businesses to anticipate coming trends and behaviors.

Sources that Provide Information to Data Miners

- Websites

- Social media

- Mobile devices

- Apps

- Internet of things

For example, data mining may show that a new model of car is selling extremely well in California but not selling at all in the Midwest. This can let the manufacturer refocus advertising and shipments to the West Coast and cut back in the heartland.

But data mining can also zoom in on your personal buying habits. If you buy a lot of birdseed online, you may see ads for bird watching supplies show up in your social media feed or while you’re visiting a website. Because you bought something in the past, data mining predicts what you might be willing to buy in the future.

Data Mining Is Different from Big Data and Data Breaches

People sometimes confuse data mining with big data or with data breaches. While all three may be related at times, each is distinctly different from the others.

Big data refers to large amounts of data, or information. Data mining refers to digging into collected data to come up with key information or patterns that businesses or government can use to predict future trends. Data breaches happen when sensitive information is copied, viewed, stolen or used by someone who was not supposed to have it or use it.

Legitimate data mining examines and analyzes information the miner has legal access to. But you may not always realize you’ve given permission for your information to be used like this. And large treasure troves of information collected for data mining make tempting targets for hackers or cyber criminals.

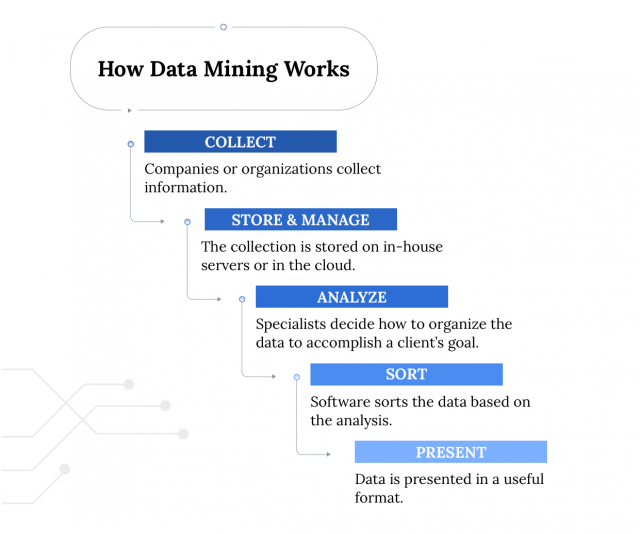

How Does Data Mining Work?

Data mining collects, stores and analyzes massive amounts of information. To be useful for businesses, the data stored and mined may be narrowed down to a zip code or even a single street.

There are companies that specialize in collecting information for data mining. They gather it from public records like voting rolls or property tax files. These can show your age, address, how much you paid for your home and how much you owe on your mortgage.

Data mining companies also buy information from websites or other businesses that track customers’ or visitors’ activities. They create profiles of potential customers that they can sell to other businesses.

How Companies Use Data Mining

- Online marketing

- Training and support

- Fraud detection

- Computerized medical studies

- Spam filtering

Profiles created by data miners may include information on millions of people. And there may be hundreds of pieces of data on each person.

Risks to Consumers

Storing a lot of information in one place can create risks for consumers. Mined data can sometimes be misused or even stolen. And just the potential for something to go wrong takes a toll on consumers.

A 2017 study from the University of Washington found that simply giving up personal information to big companies can create a rising sense of vulnerability in consumers. The researchers found when big data breaches happen, they make the feelings of vulnerability worse.

Data miners have to walk a line between creating highly useful information and protecting the privacy of the people whose data they gather. That line sometimes blurs.

Data mining has to be accurate and reliable to be useful. That means getting the most detailed information as possible. At the same time, data miners should keep the information anonymous so that you can’t be identified from the data they gather from you.

Large collections of detailed data are especially attractive to hackers. With enough information about a person, they can steal someone’s identity. The Identity Theft Resource Center reported more than 1,000 data breaches exposing more than 57 million personal records in 2018.

Experian, one of the three largest United States credit bureaus, predicts an increasing risk of identity theft in coming years as hackers target the cloud, gaming communities and wireless carriers. These are all entities where data is collected or stored.

Your Data Benefits Big Businesses

It can be difficult to keep your personal information out of cyberspace and away from data miners. Bank and medical records are digitized and can be moved around the world at the speed of light. Smart phones, apps, websites and social media can track your browsing habits, online purchases and even where you go or exactly where you are this very minute.

Data mining works partly because you agree to give up some of your privacy. It’s often a trade-off. For example, you may be willing to give up a bit of privacy in exchange for the convenience of using a debit card or credit card. But then, every time you swipe that card, the bank and sometimes the retailer collects a little more information on your behavior.

All this adds up. In 2017, one company alone, Cardlytics Inc., managed data collected from $1.5 trillion in credit card transactions. Roughly 2,000 banks sent Cardlytics purchase information stripped of customers’ personal identification.

The company sorts through the data looking for purchasing trends. Banks use this information to search for signs of fraud that could hurt their customers’ accounts. But banks also use the mined data to offer their customers coupons or improve services.

And consumers may never realize their purchases were monitored.

Online retailer Amazon uses a collaborative filtering engine, or CFE, that analyzes your purchases to predict what you’re likely to buy next. The CFE also recommends products similar to what you just added to your shopping cart. The choices are based on similar purchases by other customers.

All this mined data is turned into the power of suggestion, pushing you to make an impulse buy before you check out. Investing and financial education website Investopedia estimates these suggestions account for just over a third of Amazon’s total sales.

Facebook Shared Millions of Users’ Personal Information

Facebook raked in more than $40 billion in 2017, and user data plays a big role in the company’s profits.

Most of that money, 89 percent, came from advertising. But that advertising revenue is largely driven by your data. Advertisers can tap into Facebook’s data mining of user information to put ads in front of the people most likely to respond to them. Facebook says personal information is stripped from the process and that it keeps you anonymous.

But The New York Times reported in 2018 that Facebook gave several big tech companies, including Netflix, Microsoft and Amazon, access to various types of personal data belonging to Facebook users. This included users’ contact information, private messages and friend lists.

- All current and past Facebook friends

- All posts or other Facebook activity (likes, shares, etc.)

- Birthdate and age

- Current city

- Email address

- Every ad you click on

- Every IP address you log in from

- Gender

- Hometown

- Maiden name

- Mobile phone number

- Name

- Other social networks (Instagram, Twitter, etc.)

- Schools you attended

The Times reported that at least two “prominent makers of smartphones and other devices” had gained access to personal information of “hundreds of millions” of Facebook’s users.

Facebook and the Cambridge Analytica Data Breach

At the same time Facebook was sharing user information with tech companies, a massive data breach of users’ personal information revealed gaping holes in the site’s security and privacy protections.

Cambridge Analytica was a political data company. In 2014, it set out to gather enough information on every American voter to create extensive personality profiles on them. The idea was that it could mine this data and target people with Facebook ads tailor made for them.

The now defunct company gathered information on up to 87 million users. The company got all this information by creating a personality quiz app on Facebook. Only about 270,000 people downloaded it and took the quiz. But what they didn’t know was that by downloading it, they gave Cambridge Analytica access to the personal information of every single one of their Facebook friends.

This created a massive data set that included users’ names, ages, religion, political affiliation and both email and physical addresses.

This violated Facebook’s terms of service, and the social media giant suspended Cambridge Analytica while it investigated the privacy breach. The data company shut down after details of the scandal became public in 2018. Cambridge Analytica reported that it had deleted the data.

“Facebook is not a social media company; it is the largest data mining operation in existence.”

State’s Attorney of Cook County, Illinois, Kimberly Foxx filed a consumer fraud lawsuit against both Facebook and Cambridge Analytica in 2018.

“Facebook is not a social media company; it is the largest data mining operation in existence,” Foxx wrote in her complaint.

Facebook also faces a mass litigation in a California federal court. As of May 2019, there were 36 lawsuits over the Cambridge Analytica breach pending in the litigation.

Your Smart Phone May Be Talking to Data Miners

The Washington Post conducted a privacy experiment in 2019 to see how much personal data apps and other features of a smart phone gleaned from its user. The newspaper reported that 5,400 hidden app trackers sent data from a single phone.

App trackers are buried within the apps you download. They are quick and easy tools companies can use to mine your data. Launch certain apps, and you may unknowingly be launching several different trackers at the same time.

Is Your Fitness Tracker Tracking You?

Companies may use these trackers to improve service. But The Post investigation found some of the trackers gathered and stored data. One even collected the owner’s email address, phone number and exact GPS location in violation of the app’s own privacy policy.

Health apps on your phone or smartwatch may be sharing your health data with third parties. And in many cases, the app-maker doesn’t even warn you.

A 2019 study in JAMA Network Open found nine out of 10 depression and smoking cessation apps shared user’s data with companies like Facebook or Google, but only two out of three of the apps warned users they were doing it. The researchers found that simply sharing the name of the app with these companies was enough to disclose private medical conditions.

A 2019 Wall Street Journal report also found health apps sent sensitive information to Facebook, which could mine the data for targeted ads. The apps sent along information about users’ diet, exercise, heart rate and ovulation cycle.

While the data may be used to tailor ads to runners, dieters or women planning to become pregnant, privacy advocates see lots of room for abuse. Congress held hearings on the matter in February 2019.

“Right now, corporations are able to easily combine information about you that they’ve purchased, and create a profile of your vulnerabilities.”

Witnesses warned that health information could be sold to health care companies or even to potential employers looking for pre-existing conditions in job applicants. They also worried that insurance companies might charge consumers more if the insurers have information about poor fitness habits or unhealthy food choices.

“Right now corporations are able to easily combine information about you that they’ve purchased, and create a profile of your vulnerabilities,” Brandi Collins-Dexter from the advocacy group Color Of Change told Congress.

How to Protect Yourself From Data Mining Risks

It’s virtually impossible to avoid leaving a trail of at least some data. But you may be able to control how much information about yourself becomes available to data miners.

The first thing you should do is read over the terms of service before you sign up for any social media account, credit card or website. This will tell you about the information you’re giving up. Don’t click “Agree” unless you’re willing to agree with all the terms.

Also look at the privacy policy for any website or social media platform. This may be different from the terms of service. For instance, Facebook’s terms of service is more than 3,200 words long. It contains a two-word link to a separate data policy that is another 4,100 words long. That second page details how the company will use and share your information.

Privacy rules and laws vary by country. In most of Europe, anyone can ask any organization that collects data what information it’s gathered. The same is not true in the United States. The laws in the United States tend to give the company or group that collects the data a lot of leeway.

Check Settings on Apps, Social Media and Smartphones

Your smart phone can send a steady stream of information about you to the apps you’ve downloaded. You should ask yourself whether apps really need to know certain things about you, such as your location. Delete apps you no longer use and adjust the privacy settings on the ones you keep.

Remove personal information from social media profiles. Things like your phone number, mother’s maiden name and where you went to school are often used as security questions for apps or websites. This info simply makes things easier for an identity thief.

Check Credit Reports and Data Breaches

You should check your credit reports once a year for unusual activity. Such activity could be a sign of identity theft. The Federal Trade Commission lets you request a free copy every year.

Credit bureau Experian also lets you monitor the so-called “dark web” for signs that your information has been stolen.

The website haveibeenpwned.com lets you check for free to see if your email or user name has been caught up in major data breaches.

Consider Privacy Tools

There are several free or inexpensive options to protect your privacy online.

DuckDuckGo.com is a search engine that doesn’t collect or mine your data. Google collects enormous amounts of data about you. This includes searches, websites you’ve visited and places you’ve been when using Google maps.

HTTPS Everywhere is an app you can download that secures your online connections. This prevents eavesdropping on your browsing habits and protects you from imposters masquerading as a trusted website.

There are also several free tracker blockers available. They are installed as an add-on to your browser. The companies that make them update the blockers with information about known data trackers at different websites. The blockers then prevent those trackers from connecting when you go to a website.

Some of the more popular ones include Ghostery, RedMorph, Disconnect and Privacy Badger.

These may have drawbacks. Some may also block parts of websites you visit. That means videos may not play or links to other recommended pages may not display.

41 Cited Research Articles

Consumernotice.org adheres to the highest ethical standards for content production and references only credible sources of information, including government reports, interviews with experts, highly regarded nonprofit organizations, peer-reviewed journals, court records and academic organizations. You can learn more about our dedication to relevance, accuracy and transparency by reading our editorial policy.

- AARP. (2012, May 7). Your Life in Pixels; How Companies Are Keeping Close Tabs on Your Personal Life Through the Use of Data Mining. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/home-family/personal-technology/info-05-2012/video-data-mining-internet-privacy-ines.html

- Bergin, T. (2018, March 29). How a Data Mining Giant Got Me Wrong. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-data-privacy-acxiom-insight/how-a-data-mining-giant-got-me-wrong-idUSKBN1H513K

- Carroll, L. (2019, April 24). Health Apps May Not Disclose Sharing Your Personal Information. Reuters Health. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-privacy-apps/health-apps-may-not-disclose-sharing-your-personal-information-idUSKCN1S025Y

- Cary, C., Wen, H.J., and Mahatanankoon, P. (2003). Data Mining: Consumer Privacy, Ethical Policy, and Systems Development Practices. Human Systems Management. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/9358109/Data_mining_Consumer_privacy_ethical

- Chang, A. (2018, May 2). The Facebook and Cambridge Analytica Scandal Explained With a Simple Diagram. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/3/23/17151916/facebook-cambridge-analytica-trump-diagram

- Chen, B.X. and Singer, N. (2016, February 17). Free Tools to Keep Those Creepy Online Ads From Watching You. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/18/technology/personaltech/free-tools-to-keep-those-creepy-online-ads-from-watching-you.html?module=inline

- CIGI-Ipsos. (2018). 2018 CIGI-Ipsos Global Survey on Internet Security and Trust. Retrieved from http://www.cigionline.org/internet-survey-2018

- Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois. (2018, March 23). Kimberly Foxx v. Facebook, Inc., Case No.: 2018-CH-03868. Office of Cook County State’s Attorney. Retrieved from https://www.cookcountystatesattorney.org/sites/default/files/files/documents/cook_county_sao-facebook_cambridge_analytica_complaint.pdf

- Dance, G.J.X., LaForgia, M., and Confessore, N. (2018, December 18). As Facebook Raised a Privacy Wall, It Carved an Opening for Tech Giants. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/18/technology/facebook-privacy.html

- Dujmovic, J. (2015, March 25). How to Keep Data Miners From Invading Your Privacy. MarketWatch. Retrieved from https://www.marketwatch.com/story/how-to-keep-data-miners-from-invading-your-privacy-2015-03-25

- EDUCBA. (n.d.). Big Data vs. Data Mining – Find Out the Best 8 Differences. Retrieved from https://www.educba.com/big-data-vs-data-mining/

- Facebook. (2018, January 31). Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2017 Results. Press Release. Retrieved from https://investor.fb.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2018/Facebook-Reports-Fourth-Quarter-and-Full-Year-2017-Results/default.aspx

- Fowler, G.A. (2019, May 28). It’s the Middle of the Night. Do You Know Who Your iPhone is Talking To? The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/05/28/its-middle-night-do-you-know-who-your-iphone-is-talking/?utm_term=.6a4d8e0285ef

- Goldberg, R. (2018, August 20). Most Americans Continue to Have Privacy and Security Concerns, NTIA Survey Finds. National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Retrieved from https://www.ntia.doc.gov/blog/2018/most-americans-continue-have-privacy-and-security-concerns-ntia-survey-finds

- Granville, K. (2018, March 19). Facebook and Cambridge Analytica: What You Need to Know as Fallout Widens. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/19/technology/facebook-cambridge-analytica-explained.html

- Hsu, J. (2018, January 29). The Strava Heat Map and the End of Secrets. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/strava-heat-map-military-bases-fitness-trackers-privacy/

- Huckvale, K., Toous, J., and Larsen, M.E. (2019, April 19). Assessment of the Data Sharing and Privacy Practices of Smartphone Apps for Depression and Smoking Cessation. JAMA Network Open. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2730782

- Kang, C. and Frenkel, S. (2018, April 4). Facebook Says Cambridge Analytica Harvested Data of Up to 87 Million Users. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/technology/mark-zuckerberg-testify-congress.html

- Kaspersky Lab. (2019, April 29). Kaspersky Lab Survey Finds Cybersecurity a Top Source of Stress for Consumers in North America. News Release. Retrieved from https://usa.kaspersky.com/about/press-releases/2019_cyberstress-refreshed

- Korosec, K. (2018, March 21). This Is the Personal Data that Facebook Collects – And Sometimes Sells. Fortune. Retrieved from https://fortune.com/2018/03/21/facebook-personal-data-cambridge-analytica/

- LaForgia, M., Rosenberg, M., and Dance, G.J.X. (2019, March 13). Facebook’s Data Deals Are Under Criminal Investigation. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/13/technology/facebook-data-deals-investigation.html

- Landi, H. (2019, February 28). Collection, Use of Consumer Data Puts Sensitive Health Information at Risk, Groups Say. FierceHealthcare. Retrieved from https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/tech/collection-use-consumer-data-puts-sensitive-health-information-at-risk-groups-say

- Lapowsky, I. (2019, March 17). How Cambridge Analytica Sparked the Great Privacy Awakening. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/cambridge-analytica-facebook-privacy-awakening/

- Maheshwari, S. (2017, December 28). That Game on Your Phone May Be Tracking What You’re Watching on TV. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/28/business/media/alphonso-app-tracking.html

- Mangalindan, J.P. (2012, July 30). Amazon’s Recommendation Secret. Retrieved from https://fortune.com/2012/07/30/amazons-recommendation-secret/

- Marchini, K. and Pascual, A. (2019, March 6). 2019 Identity Fraud Study: Fraudsters Seek New Targets and Victims Bear the Brunt. Javelin Research & Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.javelinstrategy.com/coverage-area/2019-identity-fraud-report-fraudsters-seek-new-targets-and-victims-bear-brunt

- Martin, K.D., Borah, A., and Palmatier, R.W. (2017, January). Data Privacy: Effects on Customer and Firm Performance. Journal of Marketing. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305822708_Data_Privacy_Effects_on_Customer_and_Firm_Performance

- McFarland, M. (2014, October 1). The Incredible Potential and Dangers of Data Mining Health Records. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/innovations/wp/2014/10/01/the-incredible-potential-and-dangers-of-data-mining-health-records/?utm_term=.a14a040e07a8

- Menand, L. (2018, June 11). Why Do We Care So Much About Privacy? The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/06/18/why-do-we-care-so-much-about-privacy

- MicroStrategy. (n.d.). Data Mining Explained. Retrieved from https://www.microstrategy.com/us/resources/introductory-guides/data-mining-explained

- Roy, J. (2018, March 24). How to Keep Your Data Safe Without Having to #DeleteFacebook. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/business/technology/la-fi-tn-delete-facebook-data-20180324-story.html

- SAS (Statistical Analysis System). (n.d.). Data Mining; What It Is and why It Matters. Retrieved from https://www.sas.com/en_us/insights/analytics/data-mining.html

- Schneier, B. (2017, December 6). Data and Goliath: Four Ways You Can Protect Yourself From Digital Surveillance. HuffPost. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/data-and-goliath-digital-surveillance_b_6898162

- Stanley, J. (2012, April 25). Eight Problems With “Big Data,” ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/blog/privacy-technology/surveillance-technologies/eight-problems-big-data

- Statt, N. (2019, February 22). App Makers Are Sharing Sensitive Personal Information With Facebook but Not Telling Users. The Verge. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/22/18236398/facebook-mobile-apps-data-sharing-ads-health-fitness-privacy-violation

- Surane, J. (2018, August 16). Banks Are Eyeing $1.5 Trillion in Credit Card Secrets. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-16/banks-see-marketing-gold-in-1-5-trillion-of-credit-card-secrets

- Violino, B. (2017, August 25). What Is Data Mining? How Analytics Uncovers Insights. InfoWorld. Retrieved from https://www.idginsiderpro.com/article/3218151/what-is-data-mining-how-analytics-uncovers-insights.html

- Waxer, C. (2013, November 4). Big Data Blues: The Dangers of Data Mining. Computerworld. Retrieved form https://www.computerworld.com/article/2485493/enterprise-applications-big-data-blues-the-dangers-of-data-mining.html

- Williams, R. (n.d.). Examples of Data Volumes. California Institute of Technology via University of Delaware. Retrieved from https://www.eecis.udel.edu/~amer/Table-Kilo-Mega-Giga---YottaBytes.html

- Willis, J. (2018, October 20). 7 Ways Amazon Uses Big Data to Stalk You. Investopedia. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/articles/insights/090716/7-ways-amazon-uses-big-data-stalk-you-amzn.asp

- Wired. (n.d.). The Cambridge Analytica Story, Explained. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/amp-stories/cambridge-analytica-explainer/

Calling this number connects you with a Consumer Notice, LLC representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Consumer Notice, LLC's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.

844-420-1914