Dicamba

Dicamba is the active ingredient in hundreds of brands of weed killers. It has been widely used as an agricultural herbicide since the 1960s. But since Monsanto rolled out genetically engineered dicamba-resistant crops, the herbicide has been blamed for killing or damaging millions of acres of crops that have no protection against it.

Farmers in the United States have used dicamba since the Environmental Protection Agency first registered it in 1967. It was originally licensed to Monsanto, the company that also first produced the glyphosate-based herbicide Roundup. Bayer acquired Monsanto for $63 billion in 2018 and continues to produce products that contain both herbicides.

For roughly 50 years, farmers were only allowed to use dicamba on fields before planting season or after harvest to kill weeds prior to the next planting season. The chemical can damage or kill crops that are not genetically resistant to it. It can cut into harvests and farmers’ profits if it drifts onto unprotected crops.

In 2016, the EPA approved it for use on genetically modified cotton and soybean plants that have been engineered to resist the toxic effects of the pesticide. Monsanto, BASF and DuPont produce the only dicamba-based herbicides for use on growing plants.

Shortly after farmers started using the chemical on genetically modified plants during growing season, reports poured in about plants that had not been genetically modified dying. Farmers, and later federal regulators, suspected the herbicide was drifting onto the vulnerable crops.

The EPA worked with manufacturers and farmers to set up a registration process and adopt practices that would keep the herbicide from damaging neighbors’ crops. But by late 2017, more than 2,700 investigations were underway into suspected dicamba-related crop damage of 3.6 million acres of soybeans. At least two states banned its use, and it was even cited as the motive for a murder.

In 2018, the EPA decided to allow certified applicators in 34 states to continue to use the chemical on growing plants for two more years. As of March 2019, more than three dozen dicamba lawsuits had been filed in federal court on behalf of farmers who say they’ve suffered financial losses from crop damage.

What Is Dicamba?

Dicamba is a benzoic acid herbicide. It’s the active ingredient in many weed killers. The National Pesticide Information Center reports that more than 1,100 herbicide products sold in the United States contain the chemical.

Some products may also contain other herbicides mixed with dicamba. Dicamba-based products come in liquid, dust and granular forms and may be sold ready-to-use or as concentrates for mixing with other chemicals.

It is a selective herbicide, which means it is designed to kill specific weeds. It may be highly toxic to some plants but less toxic to others.

The chemical works by speeding up the growth rate of plants it targets. It acts like natural growth hormones in the plant. The plant grows too fast and in uncontrolled ways until it dies prematurely.

Dicamba-Related Crop Damage

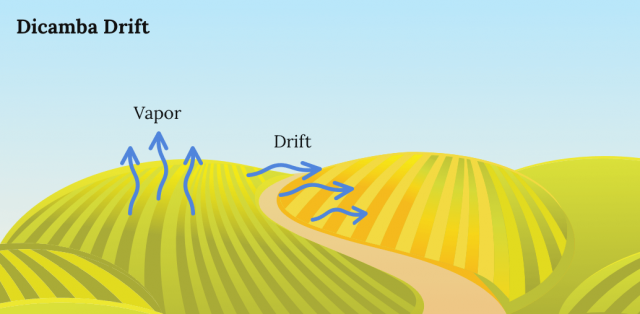

Agronomists say high winds and changes in temperature could cause dicamba to drift onto neighboring fields. The herbicide can be highly volatile in hot weather. Heat can cause it to vaporize into a gas, allowing it to drift across large areas.

By late 2017, at least 25 states had reported some degree of crop damage from dicamba. Eighteen states reported a thousand acres or more of injured soybean acreage. Arkansas alone saw nearly a million acres damaged.

The New York Times reported that dicamba wiped out 4 percent of the United States soybean crop in 2017. Missouri soybean farmer Lee Cole told Reuters in 2017 that his damaged soybean crops looked like they had been burned “by a blowtorch.”

5 States with the Most Dicamba-Injured Soybean Acres as of October 2017

| STATE | ACRES DAMAGED | OFFICIAL INVESTIGATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| ARKANSAS | 900,000 | 986 |

| ILLINOIS | 600,000 | 245 |

| TENNESSEE | 400,000 | 132 |

| MISSOURI | 325,000 | 310 |

| MINNESOTA | 265,000 | 250 |

Monsanto, BASF and DuPont are the three companies that sell the chemical in the United States for use on growing crops. The companies say people don’t always use the products as directed in the label instructions.

Monsanto’s chief technology officer, Robb Fraley, told Reuters that farmers used older, more drift-prone dicamba products, sprayed with equipment contaminated with other herbicides or applied dicamba in the wrong conditions.

Farmers’ Losses

A 2016 article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch profiled the monetary losses of farmers in Southeast Missouri from crop damage believed to be caused by illegal use of dicamba.

Soybean farmer Mark Beaird told the newspaper that dicamba damage cut his per acre yield from 65 or 75 bushels an acre to about 40 bushels on average. The damage cost him $250 per acre, which totaled about $94,000 for the roughly 375 acres he had harvested at the time. His total acreage was 1,500 acres.

“I worked this year for nothing, put it that way,” Beaird told the Post-Dispatch.

Dicamba can also damage or kill trees. Missouri’s largest peach farm suffered widespread defoliation in 2016. Its owner blamed the damage on illegal spraying of the chemical.

Bader Farms had 900 acres of orchards at the time, but nearly half of them showed damage, according to the Post-Dispatch.

Owner Bill Bader told the newspaper he expected to lose 40 percent of his crop and estimated his losses at between $1.5 million and $2 million for the year. He also said at the time that 200 to 250 acres of trees had already been permanently lost.

I worked this year for nothing, put it that way.

Farmers also had to spend money on more weed control and other efforts to save their faltering crops. Insurance companies refused to pay for damage caused by illegal spraying. The problem left farmers with no way to cover their losses except to file lawsuits.

While farmers lost money, Monsanto received a windfall. Farmers hurt by dicamba drift had few alternatives but to switch to the company’s dicamba-resistant seeds for the next planting season.

State and Federal Actions

In October 2016, the EPA launched a criminal investigation into improper use of the herbicide. The agency executed search warrants in parts of southeastern Missouri in response to complaints that dicamba drifted into neighboring fields and damaged 41,000 acres of crops.

At the time, the herbicide had only been approved for application before planting season or after harvest. But later that year, the EPA approved use of the herbicide on fields planted with dicamba-tolerant crops during the 2017 growing season.

Government regulators in Arkansas and Missouri temporarily banned dicamba in 2017 after farmers complained that the herbicide drifted to their fields and damaged crops without genetically engineered resistance. Tennessee imposed stricter rules for when the herbicide could be sprayed.

Monsanto sued Arkansas over the state’s ban but a court threw out the lawsuit in February 2018.

Also in 2018, the EPA extended dicamba’s use for “over-the-top” applications for another two years. Over-the-top means application to growing plants.

But the EPA required label changes and restrictions on who could apply it and how. The changes were to rein in risks of crop damage to neighboring fields and prevent illegal applications.

2018 Changes to Dicamba Product Labels

- Only certified applicators may apply it on crops

- No over-the-top applications on soybeans 45 days after planting

- No over-the-top applications on cotton 60 days after planting

- Applications must happen no earlier than 1 hour after sunrise and no later than 2 hours before sunset

- Cotton applications limited to two per season

- Fields must maintain a 110-foot buffer on the downwind side of the field and a 57-foot buffer around all other sides of the field

The EPA approved dicamba’s use under these rules through Dec. 20, 2020, unless the agency decides to extend the herbicide’s registration beyond that deadline.

Exposure Risks

Dicamba can cause severe, permanent damage to the eyes. People exposed in this way should thoroughly flush their eyes with running water for 15 minutes.

The Extension Toxicology Network lists dicamba as moderately toxic if ingested and slightly toxic if inhaled or applied to skin. Most people who suffer poisoning through ingesting or breathing the herbicide recover in two to three days with no permanent effects.

Symptoms of Dicamba Poisoning

- Loss of appetite

- Vomiting

- Muscle weakness

- Slowed heart rate

- Shortness of breath

- Excited or depressed behavior

- Benzoic acid in urine

- Incontinence

- Bluing of gums and skin

- Repeated muscle spasms leading to exhaustion

- Irritation of linings in the nasal passages and lungs

- Loss of voice

The National Pesticide Information Center reports that there are no data that show children have increased sensitivity specifically to dicamba. But children generally are more sensitive to herbicide exposure.

Birds are not likely to suffer harm from eating salt forms of the herbicide but acid versions can be moderately toxic to them. Several studies have found dicamba is relatively non-toxic to fish.

Animal studies have found no serious side effects from long-term exposure. Some rats that had been fed dicamba for 90 days did not gain as much weight as rats that had not been fed the herbicide. And rabbits that had the chemial on their skin for 21 days experienced skin irritation but their internal organs were not affected. Animal studies do not necessarily mean human exposure would have the same results.

19 Cited Research Articles

Consumernotice.org adheres to the highest ethical standards for content production and references only credible sources of information, including government reports, interviews with experts, highly regarded nonprofit organizations, peer-reviewed journals, court records and academic organizations. You can learn more about our dedication to relevance, accuracy and transparency by reading our editorial policy.

- Amelinckx, A. (2016, November 4). Pesticide Drift Leads to Alleged Murder. Modern Farmer. Retrieved from https://modernfarmer.com/2016/11/pesticide-drift-leads-alleged-murder/

- Bradley, K. (2017, October 30). A Final Report on Dicamba-Injured Soybean Acres. Integrated Pest Management, University of Missouri. Retrieved from https://ipm.missouri.edu/IPCM/2017/10/final_report_dicamba_injured_soybean/

- Extension Toxicology Network. (1993, September). Pesticide Information Profile: Dicamba. Cornell University. Retrieved from http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/extoxnet/carbaryl-dicrotophos/dicamba-ext.html

- Gray, B. (2016, August 14). Illegal Herbicide Use May Threaten Survival of Missouri’s Largest Peach Farm. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved from https://www.stltoday.com/business/local/illegal-herbicide-use-may-threaten-survival-of-missouri-s-largest/article_c4a4a96b-aba3-5e48-83b5-a546f5a9b8b1.htm

- Gray, B. (2016, August 5). Suspected Illegal Herbicide Use Takes Toll on Southeast Missouri Farmers. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved from https://www.stltoday.com/business/local/suspected-illegal-herbicide-use-takes-toll-on-southeast-missouri-farmers/article_af161843-b6cf-5939-beba-fc23585e8478.html

- Gray, B. (2016, September 24). Suspected Dicamba Damage Begins to Come Into Focus for Bootheel Soy Farmers. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved from https://www.stltoday.com/business/local/suspected-dicamba-damage-begins-to-come-into-focus-for-bootheel/article_da1b5b62-1b02-57df-ac7b-da70d7452d6f.html

- Gray, B. (2017, July 7). Missouri and Arkansas Ban Dicamba Herbicide as Complaints Snowball. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved from https://www.stltoday.com/business/local/missouri-and-arkansas-ban-dicamba-herbicide-as-complaints-snowball/article_2f0739e8-1b7f-5759-81b2-d78b7e249bac.html

- Lipton, E. (2017, November 1). Crops in 25 States Damaged by Unintended Drift of Weed Killer. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/01/business/soybeans-pesticide.html

- Monsanto. (n.d.). Dicamba and the Roundup Ready Xtend Crop System. Retrieved from https://monsanto.com/company/media/articles/dicamba-roundup-ready-xtend-crops/

- Monsanto. (n.d.). Dicamba. Retrieved from https://monsanto.com/innovations/crop-protection/weed-management-methods/dicamba/

- National Pesticide Information Center. (2012, February). Dicamba; General Fact Sheet. Oregon State University. Retrieved from http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/dicamba_gen.html

- Nickel, R. (2017, August 2). Drifting Crop Chemical Deals ‘Double Whammy’ to U.S. Farmers. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-pesticides-farmers/drifting-crop-chemical-deals-double-whammy-to-u-s-farmers-idUSKBN1AI1I2

- Nosowitz, D. (2018, February 20). Monsanto’s Lawsuit Against Arkansas for Dicamba Ban Dismissed. Modern Farmer. Retrieved from https://modernfarmer.com/2018/02/monsanto-lawsuit-arkansas-dicamba-ban/

- Oregon State University. (n.d.). Distinguish Between Selective and Non-Selective Herbicides and Give an Example of Each. National Forage & Grasslands Curriculum. Retrieved from https://forages.oregonstate.edu/nfgc/eo/onlineforagecurriculum/instructormaterials/availabletopics/weeds/herbicides

- Pharmaceutical Technology. (2018, June 7). Bayer Completes Monsanto Acquisition for $63 Billion. PharmTech.com. Retrieved from http://www.pharmtech.com/bayer-completes-monsanto-acquisition-63-billion-0

- Statista. (2018). Production Value of Soybeans in the U.S. from 2000 to 2017 (in 1,000 U.S. Dollars). Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/192071/production-value-of-soybeans-for-beans-in-the-us-since-2000/

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2018, November 1). EPA Announces Changes to Dicamba Registration. News Release. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/pesticides/epa-announces-changes-dicamba-registration

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Registration of Dicamba for Use on Dicamba-Tolerant Crops. EPA. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/registration-dicamba-use-dicamba-tolerant-crops

- Weinraub, M. (2016, October 25). U.S. Agency Searches for Proof of Criminal Use of Herbicide Dicamba. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-soybeans-dicamba-idUSL1N1CV2EG

Calling this number connects you with a Consumer Notice, LLC representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Consumer Notice, LLC's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.

844-255-1951